This is another strong issue, with more signs of the John Stanley to come. We see him adjusting and re-thinking his comix vocabulary. After a decade of sedate but intelligent writing on Lulu, Stanley begins to break out of the series' safe zone. He revives some of his stylistic tics from the 1940s, and hones his wit into a razor-sharp, brassy comic-book sitcom. This will be his standard operating procedure through the 1960s.

First, the cover. Lulu being bossy. Boys underwhelmed. Stanley's cartoon style is most evident in the sandbox's contents. Those warm, loose brush lines...

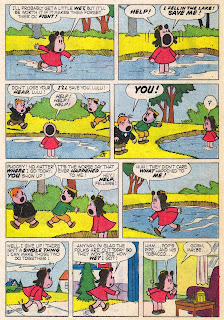

As said in Pt. 1, formulas run the Little Lulu show. Stanley set up a number of situations that he could use time and again, simply by filling in the blanks.

Among his most common set-ups is this one:

- Lulu is accused of a misdeed she did not commit, or upset by the loss of a needed object

- Tubby wanders into the picture; sees a mystery to be solved in his alias of "The Spider"

- Tubby returns with inspired-but-absurd costume; suspects Lulu's father of misdeed

- Lulu objects; Tubby insists he is right

- Tubby engages in a series of (usually destructive) actions, all of which make Lulu's already-shaky home status less tenable

- Lulu's father returns to scene of chaos; is upset; demands explanation

- Tubby accuses Lulu's father of misdeed/loss of item

- Lulu's father confesses; perfectly reasonable/mundane explanation follows

- Tubby exits victorious; if Lulu has been spanked or otherwise punished, no apology is tendered by her parents (save for rare exceptions)

Now you can write one of these stories! But, first, take a moment to read "Case of the Missing Skipping Rope," a solid late example of this formula...

Towards the end of his Lulu years, Stanley streamlined his formulae. A good pop-culture comparison are Chuck Jones' "Road Runner" cartoons. They are entirely built on rules and formulas. They become less elaborate, and more focused on cause and effect. Like Stanley's works, they focus on the highly delusional, self-obsessed anti-hero character (Wile E. Coyote), whose Quixotic actions are doomed to instant failure.

Stanley's Tubby is a much richer, more nuanced character than Jones' coyote. Tubby is a frequent victor, but he's as likely to be the victim of his grandiose schemes and his stratospheric self-regard. His deep belief that Lulu's father is a career criminal gives this series an added edge.

Stanley knew how to write to children. He connects to their value system, and offers, through his Lulu stories, an escape from their generally disempowered status. As adult readers, we still face status loss and disempowerment on a daily basis. Thus, these stories connect to our adult value system. They also provide a bridge to our earlier lives. It's a strong, silent connection that is at the heart and soul of this series.

"The Feud" is a welcome deviation from the rigid Lulu formulae. While the story has a typical series setting (the boys' clubhouse), it tweaks the typical battle-of-the-sexes plot line.

Yenta-Lulu, in her typical role of the Voice Of Reason, runs the gamut of thoughtful, creative (and socially acceptable) role-playing scenarios in an earnest attempt to reunite Tubby and Willy. Being typical stubborn males, their ridiculous grudge is surprisingly tenacious.

It takes a taboo set-up (Pop's pipe) to lure the two ex-chums out of their costume-based beef and, through the transformative powers of nausea, embrace each other.

This story has a high percentile rate of a Stanley tell: spots-before-the-eyes. This is among the few Stanley tells that were not copied by other Western/Dell writers. Stanley drags this out anytime one of his characters is made dizzy, nauseous or otherwise discombobulated.

He makes strong use of spots-before-the-eyes in his 1960s work.

Another Lulu Formula is Tubby's horrid violin playing. This is not a plot formula; it's a situation based upon an inevitable given. Tubby lacks musical talent. Like many kids of his era, he is forced to learn an instrument. He doesn't like playing the violin, and he really, really, really sucks at it.

Though even his parents acknowledge that Tub is a total wash on the instrument, they insist that he continue. His anti-music has the power to remove dental fillings, break glass, and, as seen in "Music Hath Charms," repel his greatest social foes.

"Music Hath Charms" gives us the quintessence of Tubby Tompkins. He is cowardly, arrogant, presumptuous, has a high self-regard (in the face of obvious evidence to the contrary), and inducts a kindred spirit into his exhausting scheme.

Few fictional characters can paint themselves into a corner like Tubby. Over-reaction, paranoia and a desperate need to keep his ego on HIGH are strong agents in his on-going festival of humiliation comedy.

Lulu is, apparently, no great shakes at the keyboard. I would love to hear her faltering renditions of "The Pink Panther Theme," "Fur Elise," "Linus and Lucy" and other pre-teen piano favorites. Alas, I am flesh and blood, not aged ink and wood pulp.

Staying on the Tubby tip, here's "Camping Out," a story which strongly anticipates Dunc 'n' Loo, Thirteen and other late Stanley masterworks.

It's arm-thrashing, neighborhood-rousing situation comedy here--incisively fueled by Tubby's quirks and shortcomings. Tub is similar to Thirteen's Val in his eccentric, excitable and wrong-headed behavior here.

Stanley gives us a glimpse of Tubby's parents alone in their home, obviously relieved not to have their eccentric spawn inside. Their son has interrupted many nights of rest and relaxation--just by being himself.

The story's ending has a classic Stanley touch--Iggy asks Tubby a question so obvious and essential that no one else has even thought of it. Stanley often ends stories this way. It's a clever off-beat, and it suggests there is more to this narrative that the page or printing press allows.

In this sense, the lives of the characters continue in the reader's mind. This may account for the enormous appeal of Stanley's Lulu cast. Like Charles Schulz's and Daniel Clowes' characters, they have a life beyond their two dimensions and the still-frames of their comics panels.

Color note: I'm a devotee of night-time scenes in color comics. Always have been. Thus, I dig the very simple but creative suggestion of night in this story's last page. Western's crude presses could not offer much in the way of color variance. The uncredited colorist solved the problem very well here.

Western's particularly monotonous color palette becomes part of the narrative rhythm of Stanley's Little Lulu. Lulu's dress is always that raw magenta; Tubby's tie is a constant flat cyan. The grass is usually a parched yellow. Trees and shrubs are two flat shades of green. All browns are the same fecal shade.

The unvaried colors reinforce Stanley's strong characterizations and settings. Inevitably, Lulu loses much of its impact in black and white. The popularity of the Dark Horse black-and-white books (which I see in almost every household I visit that has kids) is a credit to the compelling aspects of John Stanley's comedic and narrative sense.

4 comments:

Surprisingly (to me) these really are good stories, despite their relatively late publication date. Also, from now on, whenever you refer to Stanley "tells", I think you should call them Stanley "earmuffs".

I'm wondering if you could shed some light on the reprinting of the Tubby books. Dark Horse and Drawn & Quarterly have both announced collections. Will they overlap?

Publishing history is littered with little cul de sacs. Comic books are particularly "saccy."

Some issues of TUBBY are in the public domain, and some had their copyrights renewed by the current owner of the property. (I'm not 100% sure who or what that entity is, so I won't attempt to name them/it.)

I don't know if the Dark Horse books will duplicate the material in the Drawn + Quarterly. Neither company's reprint projects attempt to create facsimile covers, or otherwise call significant attention to the issue number of a particular comic book.

I almost hope there is duplication. It will concretely show the differences in the two publisher's archival reprint methods.

As I've said before, I find Dark Horse's reprints to err on the side of contrast and brightness. Drawn + Quarterly are still working to perfect their approach to archival comic book reprints, but their reproductions are far more faithful to the original. They're much easier on the eye, as well--they faithfully reproduce the pastel palate of the original comic books.

The finale of this long-winded reply: I honestly don't know, but I'm curious to find out.

I did some digging and from what I can tell, the first Dark Horse book of Tubby reprints will handle issues 1-6, while the Drawn & Quarterly volume will contain issues 9-12.

Post a Comment